Reports of dire conditions in U.S. immigration detention

It was accompanied by a screenshot of a photo of a man with swollen red eyes, with another screenshot of his full detainee information.

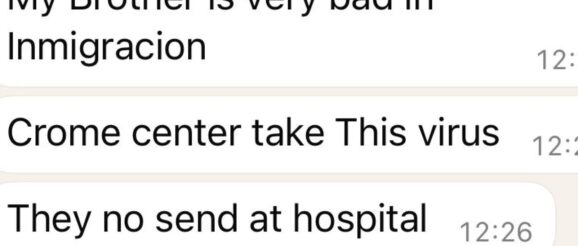

“Please help me. Im desperate.”

The woman who sent it, Maria, was texting about her brother at the Krome Detention Center in Miami. She requested their last name be withheld, for fear of retaliation against her brother who has been held in detention for more than two months.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

“I had a client who was at Krome,” says Miami based lawyer Jeff Botelho, whose client recently told him that “they had been sleeping on the floor for a week or two. For food he said they were given a cup of rice and a glass of water a day. It was very concerning.”

“There’s incredible pressure to ramp up arrests inside the interior of the United States,” says Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), a noofit immigrant advocacy group. He estimates that ICE is at 125% detention capacity. “And so far, there has been, if anything, just a slight increase in the capacity to actually deport people.”

What do the detention and deportation numbers say?

The increase to nearly 50,000 detainees marks a sharp increase from the number of detentions during the Biden administration, which climbed to 39,703 in January 2025.

Syracuse University professor Austin Kocher, who tracks immigration statistics, notes that immigration arrest numbers are simply not made available by local or federal officials.

Deportation numbers are even trickier to come by. The government claims it has deported more than 160,000 people since Trump took office for a second term in January. Some experts are skeptical that those figures are accurate.

“Up until about three weeks ago or so, things were pretty consistent with what they were in terms of the end of the Biden Administration,” says Tom Cartwright, who has been tracking deportation flights for years. “Typically four to five deportation flights per day.”

But Cartwright says that number has increased in the last few weeks to six to seven flights a day, mostly to Central America. And while he has no way of knowing how many people are in each airplane, he calculates each plane has the capacity to carry between 120 and 150 people.

At most, that’s an estimated 1,050 people being deported every day out of the 50,000 or so who are detained.

Overcrowding, illness and hunger reported in detention facilities

Advocates say this situation is playing out nationally.

“We have seen a rapid deterioration over the last few months,” says Setareh Ghandehari, advocacy director at the noofit advocacy group Detention Watch Network. “We’re hearing reports … that there isn’t enough food.” She says she’s increasingly been hearing accounts from people in detention going hungry. “I’ve heard people use the word ‘starving.’ “

There have been nine deaths in ICE detention since January, which is on track to be the deadliest year since 2020. At least three of those deaths have been in Florida.

Major expansion of detention facilities coming

The Trump administration is promising to increase the rate of arrests of immigrants to 3,000 people a day. “President Trump is going to keep pushing to get that number up higher each and every single day,” White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller told Fox News last week.

Miller was discussing the sweeping budget bill passed by the House and now before the Senate. It would provide $75 billion over the next couple of years in additional funding for ICE, including $45 billion for detention facilities and $14.4 billion for removal operations.

“We can have, permanently, the safest, strongest, most secure system in American history,” Miller told the network.

But immigrant advocates warn the measure will expand mass detention and surveillance.

“I think that it is not designed to increase the removals of people who are not legally allowed to be here,” says Deborah Fleischaker, former acting chief of staff for ICE during the Biden administration. “It is designed to hold more people for longer.”

Fleischaker believes ICE has historically been underfunded. But she says the bill as written “is so significant and so extreme. What they’re trying to enable … I don’t think it is within the imagination of the American people when they voted for Donald Trump.”

Isacson of WOLA adds that the actions occurring now will multiply. “Plainclothes people using rough tactics and covering their faces to take people off the streets and sort of muscle them into vehicles,” he says. “This is going to be common. And it’s going to become much more common to see that all around the country military bases may have detention facilities.”

“What are the chances my deportation flight will make a wrong turn?”

“I am anguished. I have not heard anything about my son.”

Jhonkleiver Ortega came to the U.S. three years ago and was working in construction. He was picked up while driving in November 2024 for not having a license, which under Florida state law is not available to immigrants without legal status. She told us she had sold her house in Venezuela to pay for his $7,000 bond in January. When he went to his next court hearing in February, he was detained.

Vivian had heard from him infrequently, and she was terrified “he was barely eating in there.”

Data trackers and policy experts say the Trump administration’s goal of deporting one million migrants a year is so high that encouraging self-deportation is paramount. “The fact that [detention] is often so unsafe and unhealthy leads me to believe that there’s also a desire to wear people down,” says Isacson.

High-profile flights — with migrants sent to the U.S. naval base in Guantanamo, Cuba, and to El Salvador’s notorious detention center CECOT and, more recently, a flight headed to South Sudan — have sent a strong message. For Vivian, the possibility was a source of constant anguish.

“They told me they had to review my asylum case,” Ortega told his mother. “They told me I have to send proof that I was tortured in Venezuela. And in four months they would give me an answer. And I said I can’t anymore. It’s been months of this. They barely feed us here. I can’t anymore. I asked to be deported. This week or next I will be on a flight to Venezuela. If they give me a call from Louisiana I’ll call you before the flight.”

“What?” his mother asks.

“I asked the judge what are the chances that my flight will get lost and accidentally end up in another country? And she said if that happens you call the deporter. Or email me.”