New data reveals the inadequacy of FEMA flood maps

Maps by First Street, a climate risk modeling company in New York City, show at least 17 structures in the path of flood waters, compared to maps produced by FEMA, highlighting a longstanding risk facing many Americans. The analysis also shows at least four cabins for young campers were in an area designated by FEMA as an extreme flood hazard, where water moves at its highest velocity and depth.

For decades, FEMA’s maps have failed to take rainfall and flash flooding into account, relying instead on data from coastal storm surges and large river flooding, even as climate change is supercharging rainfall intensity. Nationwide, First Street found more than twice as many Americans live in dangerous flood-prone areas than FEMA’s maps suggest, leaving many homeowners and even local officials unaware of the risk.

“The unknown flood risk is bad from a preparation, financial standpoint, but there’s a human element here that often gets overlooked,” said Jeremy Porter, head of Climate Implications at First Street.

FEMA’s maps can serve as critical warnings to the public about potential danger, but they are also one of the few ways the federal government can require people to take precautionary measures. FEMA requires homeowners in certain flood prone areas to build in ways that could help them withstand a flood, often by elevating their homes.

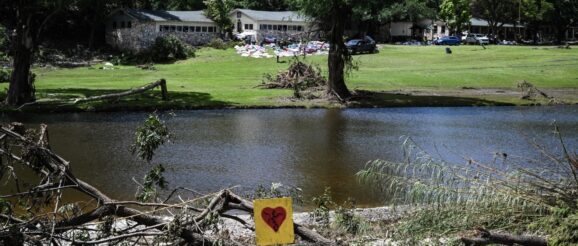

But in recent years, many properties affected by disasters are turning up outside FEMA’s floodplains. When Hurricane Helene struck western North Carolina last year, 98 percent of the damaged homes were not included in FEMA’s maps. This meant that not only were most homeowners unable to claim flood insurance, most of them had not been obligated to build in a way that could have helped them better survive the storm.

FEMA has known about this problem for years, but the agency lacks the mandate and funding from Congress to address it, according to Porter.

“You think in principle people would say we should have better flood coverage, look what just happened,” Porter says, “but it’s so heavily politicized that you can’t get anybody to bring it forward because they don’t want to be the people that raised flood insurance costs.”

Outdated FEMA maps played out in a significant way along the Guadalupe River in Kerr County. Using FEMA’s data, First Street found just 2,560 homes at risk in the area. Using their own data, the group discovered more than 4,500 homes were actually in danger.

While many of the camp’s cabins may date back nearly a century, FEMA imposes strict limits on development in these areas, and often outright prohibits it altogether.

“No one should be in a floodway,” says Jim Blackburn, co-director of the Severe Storm Prevention, Education and Evacuation from Disaster Center at Rice University in Houston. “Floodways are the most dangerous of a danger zone.”

Camp Mystic’s dining hall, recreation hall, and four cabins all appear to be in the floodway, less than a couple of hundred feet from where the river makes a tight bend.

Blackburn says it’s been difficult to get Texas officials to act on the severity of the threat from floodways and floodplains.

“In Texas, we don’t think the floodplains are that serious,” he says. “We treat floodplains as a kind of good old boy, kind of wink and nod, [as though] it’s environmental red tape. And that’s going to get a lot of people killed.”

Chad Berginnis, head of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, said that recent delays with grants and agreements have impeded state and local efforts to better map flood risk in their communities, adding that cuts from the Trump Administration could make it even harder.

“When I look at the flood map in the area of Camp Mystic, there is a small water course that comes in right there that doesn’t have good flood mapping data,” he says. “The action is simple. Get the notice of federal funding opportunities out and get those grants approved for funding. Those are things right off the bat that the administration could do.”

Blackburn, from Rice University, says it’s no longer helpful for officials to call these events rare, or uedictable. He says while no one can know which area will be hit next, the risk is known and communities should prepare for a catastrophe.

“It is happening,” he says. “The science is solid. What we need is reasonable decision making based on the best available science and we don’t have that right now.”