Goats and Soda

About two decades ago, Namibia was one of the hardest-hit countries in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. More than one in three adults tested positive for HIV.

Dr. Mark Dybul remembers visiting a clinic in rural Namibia and meeting a woman and her baby. She was HIV-positive and was terrified of passing the virus on to the child. She named her baby No Hope in the local language.

“That’s one of the most devastating things you could ever hear,” Dybul says.

A game changer

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, soon changed everything.

President George W. Bush created PEPFAR in 2003 and reauthorized it in 2008. Dybul was the principal architect of PEPFAR while he was at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and he was later appointed U.S. global AIDS coordinator.

PEPFAR has since given out billions every year to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with programs like free drugs to prevent mother-to-child transmission and widespread treatment of HIV-positive people to keep the virus from progressing to AIDS and to keep it from being spread to others.

The State Department has credited it with saving 26 million lives so far.

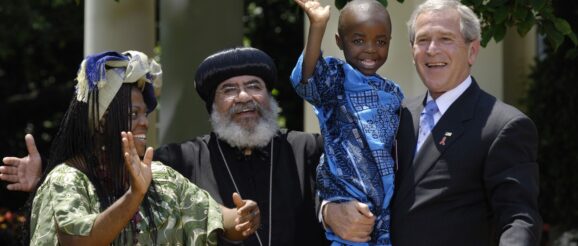

Alex Wong/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

What will happen to PEPFAR?

Now the future of PEPFAR is hazy. On Tuesday, President Trump asked Congress to rescind $8.3 billion in foreign aid that lawmakers had already approved in 2024 and 2025 budgets — including $400 million allocated to PEPFAR.

The cuts would drastically reduce work on HIV and other infectious diseases.

The move would codify cuts already made by the U.S Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which dismantled USAID and absorbed it into the U.S. State Department in the first months of Trump’s term and dramatically reduced PEPFAR’s reach.

Congressional decision awaited

Congress now has 45 days to respond to Trump’s memo.

The move comes after a March ruling by U.S. District Judge Amir Ali that the Trump administration acted “unlawfully” by halting foreign aid without Congress’s approval.

The rescission request “put the ball squarely in Congress’s court,” says Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, an HIV prevention organization receiving PEPFAR funds that led the lawsuit.

“Congress, at least to date, has moved not at all. The question really is, will they act?” Warren asks.

Some members of Congress have signaled they want to keep PEPFAR from being slashed — so PEPFAR’s future is still uncertain.

Nonetheless, it has been an up-and-down year for PEPFAR. The program’s work was initially halted in the days following Trump’s inauguration.

A few weeks later, Secretary of State Marco Rubio instructed PEPFAR to resume operations again — but only or treatment of existing HIV-positive patients and HIV prevention measures for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

That doesn’t represent everyone at risk for HIV infection.

There are still 1.3 million new HIV infections every year, which means the pool of people who need treatment will grow rapidly without more prevention, Warren says.

These cuts do “exactly the opposite of what this administration says they want to do, which is to get countries to own their AIDS response and own their budget,” Warren says.

“We all want to see that transition, but we’re making it harder for countries by not helping them reduce the burden of treatment programs. And in fact, we’re going to add to it.”

Dybul agrees.

“Eventually we should be in a position where there is no PEPFAR. But it can’t be done overnight,” Dybul says.

He still remembers how “absolutely catastrophic” HIV was only a few decades ago.

The epidemic was particularly brutal because HIV often kills young people in the prime of their lives, Dybul says.

“You would have entire villages run by orphans because all the adults were gone. Countries could have ceased to exist. That’s how devastating it was.”

Programs like PEPFAR have saved lives, built health systems and made hard-hit countries like Namibia more stable, he says.

And U.S. assistance also offered hope, Dybul says. Because of PEPFAR, “no one would any longer name their child No Hope,” he says.

Without it, there “is a hopelessness that occurs when you see everyone dying around you, you think you’re going to die,” Dybul says.